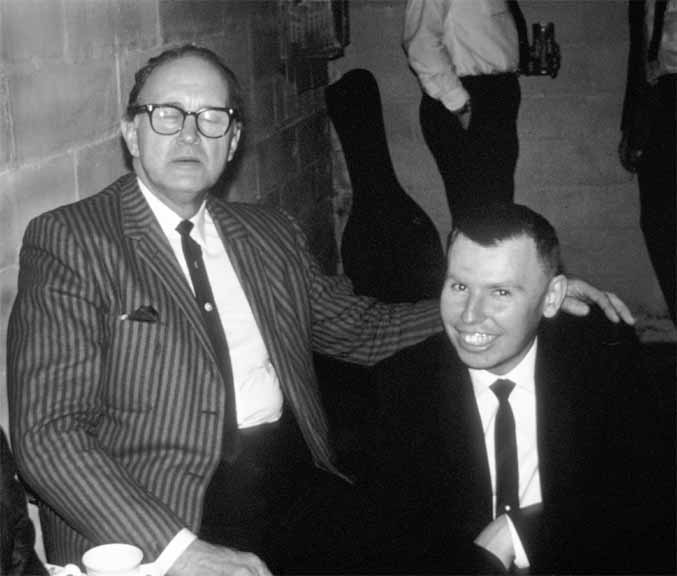

Apres-concert party, 1964. Standing (L-R): Tracy Schwarz, Roscoe Holcomb,

Mike Seeger, Willie Johnson. Seated: Liz Lofgren, Lyle Lofgren, Jon Pankake,

John Cohen, Dock Boggs (photo: Mary Alice Walker).

|

Note: This article (copyright 2002, The Old Time Music Group, Inc.) was originally published in The Old Time Herald, Vol. 8, No. 6 (Winter 2002-2003), and is reprinted by permission. We recommend that you subscribe to the Old Time Herald. It's finger-lickin' good. |

|

Uncle Willie & The Brandy Snifters: a legendary band? If you've heard that we're legendary and hope to find out why, here's how I think the rumor got started. Unlike our urban cohorts, we never scoured the South looking for "lost" musicians. Like many of those seminal musicians, the place you'd be likely to find us would be at home. If scarcity increases desirability, we must be very valuable. Saturday morning, Jon Pankake's living room. Jon, Bud Claeson and I are present. Marcia Pankake otherwise occupied. Willie Johnson can't bear to come. Two tape recorders cued up. One holds a 7-inch reel from Willie's collection with a tape list coded with colored ink according to his taste. The best -- Grayson & Whitter or Earl Johnson & his Dixie Clodhoppers, for example -- is a Red A, and costs a dollar. Blue As, marred by hiss and scratch, are fifty cents. Green Bs -- anything with yodeling or by performers such as Milton Brown and his Musical Brownies -- go for thirty cents. Brown Ss are free. A blank reel on the second recorder is ready to be filled with dubs we choose to buy. To ease decision tension, a quart jar of Georgia Moon, clear corn whiskey guaranteed to be aged less than 30 days, sits on the coffee table etching a permanent ring. Jon flips the switch and we sample a song of questionable merit, Reno Blues by the Three Tobacco Tags. "Time to vote, thumbs up or down." We buy the song. Later, we'll grow fond of many such marginal choices and learn them as band pieces. The more Georgia Moon we imbibe the better we like the music -- even green Bs and, God forbid, brown Ss. After several rounds of voting, we pass up home cooked Minnesota victuals for Southern sustenance. I'm sent out for an order of Colonel Harlan Sanders's fried chicken with biscuits and extra gravy, which I drink straight from the container while the others look on in awe. Minneapolis, late '50s: From sea to shining sea you can hear Pete Seeger's banjo ring and it's hip to learn How To Play The 5-String Banjo. Our midwestern hearts swell to the passion of The Weavers, which whets our appetite for something more. Convinced by Pete that anyone can learn to play and sing, even though I couldn't master the Swedish-American tunes my father played on the fiddle, I buy a Stella 6-string guitar. A youth spent hand-milking Holsteins gives me the strength to squeeze the chords. Later, he gives me one of his fiddles, but I abandon his tradition to see-saw Appalachian style. Meanwhile, Bud is spending winter nights listening to Grand Ol' Opry on the ionospheric skip from Nashville, following along on a Silvertone archtop guitar. We meet and pool our musical tastes. Then we discover the Minneapolis Public Library has a remarkable old-time music collection. Its quality is a side effect of Willie's influence on the music librarian, his long-time friend Mary Alice Walker. If you were to look in on a library sound booth in 1960 you would see Bud and me sharing earphone halves listening to Pete Steele on Library of Congress recordings. We take out New Lost City Ramblers (NLCR) records and try out their songs together. Fall 1959: Liz and David Williams, whose tastes are honed on The 1952 Folkways Anthology, arrive from Oregon, toting 2 Stewart banjos. They want to gather everyone together who loves this kind of music, and within a week lure Willie from his garret, starting a tradition of Friday night parties for locals and performers passing through town. Liam Clancy, for example, is impressed that Willie can match him song for song until dawn, singing an American version for every Irish song Liam sings. About this time, Jon Pankake and Paul Nelson put out the first issue of an acerbic arbiter of taste, their Little Sandy Review. In addition to encouraging real traditional music, they write devastating reviews making sport of urbanites who make fast bucks off the folk music craze. They manage to infuriate professional musicians to a level disproportionate to the magazine's miniscule circulation. Paul also works for the local music distributor, so the city's largest record store has a bin containing the Folkways Anthology, as well as NLCR and Bascom Lunsford LPs. At one Friday night party, Bud and I meet Willie and start to play along with him. Because he is our mentor, has words to songs the NLCR haven't heard yet, and also because he's older, we give him the honorary title Uncle Willie. We sponsor break-even NLCR concerts so we can hold parties afterwards. We press an LP of Gid Tanner & the Skillet Lickers reissues (FSSM 15001-D), using material from Willie's tape collection. We find a musician who started to make his own album but ended up only with blank white cardboard sleeves. We buy them and paste on a crudely-printed label, originating the tradition of white sleeves to signify bootleg albums. We press 250 copies, and sell almost all of them at the Chicago Folk Festival. The remainder go by mail order, mostly to Australia and New Zealand. Liz sends a copy to Nat Hentoff, who reviews it in The New Republic along with the first Bob Dylan album—an unfortunate juxtaposition. Anxious to read favorable reviews of their fledgling star, Columbia stumbles on the review of our pirated re-issue of their long forgotten former recording star, Gid. We receive a cease-and-desist letter from their legal staff. Plans for a second album are scrapped when we decide to comply. Out of the bootleg publishing business, the Society lasts for a few more years and NLCR concerts before folding. As of 2002, Columbia still hasn't reissued Gid's recordings.

We don't stop playing. We regularly assemble in a living room, tune up, and Willie sets up some words on a music stand. We argue over HWCATDI (How Would Cranford And Thompson Do It) arrangements and words ("Get 'em right," says Willie). We try to imitate our heroes, but things go awry. I can't bow or finger as well as Arthur Smith, so I substitute something easier. Willie clawhammers the banjo instead of fingerpicking, or vice-versa. Jon plays mandolin like Ted Hawkins rather than like Bill Monroe. Bud throws in syncopated Riley Puckett runs, leaving Marcia to steady the rhythm and supply the chords with her second guitar. Even when we try our best to imitate, the result is different from the original.

Then it's over. Walker needs more money to support its modern dance presentations, and so produces rock concerts instead. |

|

Accustomed to clustering around a Tandberg mike taped to a broomstick, we're not used to being spread out across the stage like this. "Can't we put all the microphones together in the middle so we can hear each other?" "You can hear through the monitors. If we did it your way, you'd poke each other's eyes out with your fiddle bows," says the sound man. We can't hear anything from the monitors. Kirk McGee once told us that he and Sam practiced keeping in time by starting a tune, then each walking opposite directions around the house to see if they were still together when they met again. I can't even start in time with the others, trying to watch their hand movements. By the time we figure out how to keep together, our 30 minutes are up. The audience still hasn't returned from dinner. A friend in the audience tells us that the sound man was trying to give each of us instrumental solos by adjusting volume on different mikes, but was confused because we were all playing the tune at the same time. |

|

"Let's play Bearcrap in the Buckwheat," says the expert fiddler. "I don't know that one," I say. "It's in F, then goes to A minor, and the bridge is in B-flat." I pretend to fiddle along for 20 minutes. Then I say, "Let's play Diamond Joe." Nobody else has heard it before, but it's in the key of G so they catch on immediately. I try to sing Gonna buy me a sack of meal, Take my hoecakes to the field, Diamond Joe, better come get me, Diamond Joe. But I can't hear what I'm singing. No one else can either, because they're all playing as loud as they can. I give up, and after a minute, we stop playing because the tune in this crowd is too boring. We start another, more complicated one.

on the back. We put so much energy into the jackets that we forget to line up a celebration concert. We once tried to expose people to music they wouldn't otherwise hear. Our performances were not as good as on the original recordings, but we used a similar approach. The originals, after all, were so bad acoustically that few would listen to them. With companies such as Shanachie/Yazoo, Rounder and County re-releasing acoustically improved recordings that were previously only in private tape collections, we're no longer needed as musical missionaries. But we're the band that proves Pete Seeger right. Anybody can play this music. As Jon says, it's the second most fun you can have without laughing out loud. If you're inspired to teach yourself to play, you don't want to start by emulating Doc Watson on guitar or Eck Robertson on fiddle. You should aspire to an achievable goal -- to play like a Brandy Snifter. Just be careful not to let your ability outrun your talent. Over 40 years have passed and we still meet in the living room. The Georgia Moon has disappeared along with our youthfulness. The two guitars and banjo drive the music so it flows without effort, very different from the exertion of practicing alone. It bounces off the ceiling into my ears. My arms, fingers and throat respond by themselves. Bud's high tenor sends shivers through me. No matter how bad or good I feel, playing in the band makes me feel better. Tax returns, investment decisions, engineering calculations are all light years away as I ride the sounds back through the uncountable generations that produced and preserved them. And we're still part of that process, even if hardly anyone else gets to hear us. As Jon wrote in the notes to String Band Project: |

|

Jan. 28: New Lost City Ramblers; Dock Boggs; Roscoe Holcomb Feb. 8: Bessie Jones & Georgia Sea Island Singers; Mississippi John Hurt; Sleepy John Estes w/ Hammie Nixon & Yank Rachel Feb. 22: Jean Ritchie; Doc Watson w/ Fred Price & Clint Howard 1965: 1966: |

|

Hallelujah To the Lamb The Burial of Wild Bill What Will I Do, For My Money's All Gone? I Got A Gal in Baltimore On THE MARIMAC ANTHOLOGY: DEEP IN OLD TIME MUSIC,

Rounder CD 0364: GOING NOWHERE FAST, Lak-O-Tone CD Minus 001, reissue of Marimac cassette 9005 (1986) NOT OUT OF THE WOODS--YET(2003), Lak-O-Tone CD Minus 002. VOICE OF THE PORKCHOP (2007), Lak-O-Tone CD Minus 003. PRACTICE

NIGHT WITH |