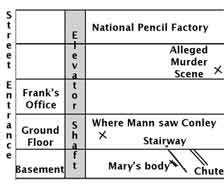

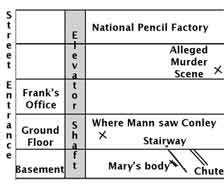

Sketch, from the side, of the National Pencil murder scene,

based on contemporary drawings.

There is a tendency among Old-Time musicians to think that our music is Fine and Upstanding and (as A. P. Carter would have put it) "morally good." But it's not always true. This month marks the ninety-sixth anniversary of a tragedy and a travesty of justice, and this month's song sadly preserves the injustice. The only real use for this song is to remind us that we need to examine data, not open ourselves up to prejudice.

You'll have to forgive me if I get a little wrought up in the course of this article; it is a vile tale. I've read three books (by Dinnerstein, Frey/Thompson, and Oney), on the murder of Mary Phagan and the judicial murder of Leo Frank, plus articles, and each one makes the tragedy worse. Warning: This is close to an R-rated account.

Mary Phagan was born in Marrietta, Georgia. Because her father was dead, she had to leave school at the age of ten to work in a factory. (Georgia had no child labor laws then.) She went through several factory jobs as a pre-teen.

In 1913, when Mary was not quite fourteen, she was working at the National Pencil factory in Atlanta. She normally worked fifty-six hours a week for about ten cents per hour. On the week of April 26, 1913, however, there was a supply glitch. The workers in Mary's department (mostly teenage girls like Mary) were forced to take time off without pay.

Although Saturday was a workday at National Pencil, Saturday, April 26 was Confederate Memorial Day -- a Georgia holiday. National Pencil paid its workers on Friday and closed down on Saturday. Mary, since she had not been at work, did not know that she could have been paid early. That Saturday, she took the streetcar to collect her money. She planned after that to watch the holiday parade.

Around noon, she entered the almost-deserted factory (which was rarely locked), picked up her pay from plant manager Leo Frank -- and was never seen alive again.

Around 3:00 a.m. the following morning, night watchman Newt Lee went down into the cavern-like basement to use the colored toilet. (Atlanta in 1913 of course had segregated restrooms!) There, he found the body of Mary, with a bloody wound in her head, cinders in her mouth, cuts and dirt all over her body, her fingers torn out of joint, marks of strangulation on her neck, her clothing torn, and a shred of her undergarments around her neck. It was clearly murder of the most brutal kind.

The suspicion was that it was rape as well -- Mary was a beautiful girl, with reddish-blond hair, a pretty face, and a good figure; she was said to be the most attractive girl in her neighborhood. The physical evidence was not sufficient to bring a claim of rape -- but it hardly matters; in a town where the administration winked at prostitution and the phrase "white slavery" was common in the newspapers, everyone suspected it. Few paid much attention to the fact that Mary's handbag, containing her pitiful wage (thought to have been $1.20), was missing.

The Atlanta police department at this time was hardly deserving of the name -- it took only one week's training to join the force. In their "investigation," they found National Pencil janitor Jim Conley with blood on his shirt. But the man charged with murder was National Pencil manager Leo Frank.

Did Leo Frank have a motive? It wasn't robbery; he made at least six times as much money as Mary. It probably wasn't sex, since he was happily married. And he was a small, birdlike man, not much stronger than Mary -- he could hardly have overpowered her, and if he had tried, there would have been bruises on his body. There were none. Moreover, Frank had alibis for much of the period in which the murder could have been committed. (The time could not be definitely established with 1913 methods, especially by the untrained Atlanta police.)

Jim Conley, confronted with the evidence against him, testified that Frank had committed the murder and told the janitor to dispose of the body.

Conley was a known petty criminal, who had been imprisoned repeatedly while in the employ of National Pencil. He changed his story at least four times, each time adding details to make Frank sound more guilty. There is evidence that he had been coached in his testimony. He demonstrably lied about at least two key points. But he wasn't Jewish.

When the case came to trial, solicitor H. M. Dorsey, who managed the prosecution, asked every witness about Leo Frank's sexual behavior. Almost all denied that Frank was in any way aonormal -- but the insinuations reached the jury. The end result: They unanimously convicted Leo Frank of murder.

Judge Roan would later write that he wasn't sure Frank was guilty. He sentenced him to death anyway.

Naturally there were appeals. One was denied on grounds of lack of jurisdiction. Another was denied on the grounds that mere innocence was not grounds for appeal (I'm not making this up). Thus, to have a stupid lawyer -- as Leo Frank had had -- was a capital crime.

The Georgia Supreme Court claimed there was no reason to intervene. They did this even though, by this time, several sources had come forward with compelling evidence that Jim Conley had murdered Mary Phagan. One of the sources was Conley's lawyer (Conley had been given a short prison term as an accessory and hence was considered safe from a murder charge; it would be double jeopardy).

A majority of the United States Supreme Court refused to take up the case.

Only one man with jurisdiction -- Georgia governor Slaton -- had the integrity to risk his political future to save an innocent man. He didn't dare set Frank free, but he did commute Frank's sentence to life in prison. A few days after, when his term ended, Slaton fled the state for fear of lynching.

Slaton wasn't the only one who had to fear death. Soon after, a fellow inmate slashed Leo Frank's throat. Frank survived, barely, but a few weeks later, an informal army (with weapons and automobiles and equipment for breaching the defences) attacked the prison where Frank was being held. They kidnapped him, drove him to the town where Mary Phagan had grown up, and hanged him on the night of August 16, 1915.

Although most of the lynchers were known, not one was ever brought to justice.

Jim Conley, as far as we know, never committed another murder. But he continued to be imprisoned on charges related to drunkenness, theft, and petty violence. Not only had Georgia justice convicted an innocent man and encouraged his lynching -- but it had also left a murderer loose to commit further crimes.

And all, it appears, because Leo Frank was a Jew. I can't help but note that, had Leo Frank lived to a normal old age, he would have seen the establishment of the state of Israel, now considered a close ally of the United States.

Some seventy years after Mary Phagan's death, Leo Frank's name was finally cleared. A young man, Alonzo Mann, had seen Jim Conley carrying Mary's body at the time of the murder, and at last told his story shortly before he died. It took three years after that, but Frank was at last declared innocent.

The evidence of his innocence (little of which is recounted here, despite the length of this article) had been there all along, except for Mann's testimony. It is frightening to realize how good we are at seeing what we want to see.

This song, of course, was written before Leo Frank was cleared -- very possibly before he was lynched. It is likely, though not certain, that it was written by Fiddlin' John Carson, and certainly his daughter was the first to record it. The first collected version comes from a 1918 volume of the Journal of American Folklore. That is essentially the text printed here.

I don't sing this song -- after all, it claims Leo Frank was guilty. I use it instead to justify that phrase interjected on so many old time recordings: "Take Warning!"

Because this article is so long, I'm not going to print the tune. You'll probably know it anyway; it's Charles Guiteau, which was printed in the July 1997 Inside Bluegrass.

Complete Lyrics:

Little Mary Phagan,

She left her home one day;

She went to the pencil factory

To get her little pay.*

She left her home at eleven,

She kissed her mother goodbye;

Not one time did the poor child think

That she was a-going to die.

Leo Frank he met her

With a brutish heart, we know;

He smiled and said, "Little Mary,

You won't go home no more."

Sneaked along behind her

Till she reached the metal room.

He laughed, and said, "Little Mary,

You have met your fatal doom."

Down upon her knees

To Leo Frank she pled,

He taken a stick from the trash-pile

And struck her across the head.

Tears flow down her rosy cheeks

While the blood flows down her back;

Remembered telling her mother

What time she would be back.

You killed little Mary Phagan,

It was on one holiday;

Called for old Jim Conley

To carry her body away.

He taken her to the basement,

She was bound both hand and feet;

Down in the basement

Little Mary she did sleep.

Newt Lee was the watchman

Who went to wind his key;

Down in the basement

Little Mary he did see.

Went in and called the officers

Whose names I do not know;

Come to the pencil factory,

Said, "Newt Lee, you must go."

Come, all you jolly people

Wherever you may be;

Suppose little Mary Phagan

Belonged to you or me.

Now little Mary's mother

She weeps and mourns all day,

Praying to meet little Mary

In a better world someday.

Now little Mary's in heaven,

Leo Frank's in jail,

Waiting for the day to come

When he can tell his tale.

Frank will be astonished

When the angels come to say,

"You killed little Mary Phagan;

It was on one holiday."

Judge he passed the sentence,

Then he reared back;

If he hang Leo Frank,

It won't bring little Mary back.

Frank he's got little children,

And they will want for bread;

Look up at their papa's picture, Say,

"Now my papa's dead."

Judge he passed the sentence,

He reared back in his chair;

He will hang Leo Frank,

And give the Negro a year.

Next time he passed the sentence,

You bet he passed it well;

Well, Solister (sic.) H. M.

Sent Leo Frank to hell.

* The JAFL version reads, "To see the big parade." Mary did want to watch the Confederate Memorial Day parade, but that isn't why she went to the factory. The line printed here seems more common anyway.