'NOW WHERE WAS YOU LAST FRIDAY NIGHT, WHILE I WAS LOCKED UP IN JAIL'

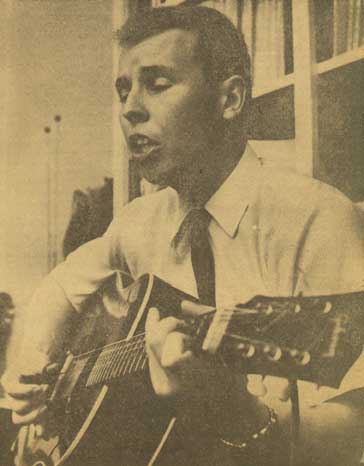

Mrs. Ann Bushnell plays guitar, sings, with Folk Song Society of Minnesota

|

Come all you good people, I'll sing you a song,

I'll tell you the truth, I know I ain't wrong

It's from father to mother, from sister to brother,

They've got in the fashion of cheating each other,

And it's hard times.

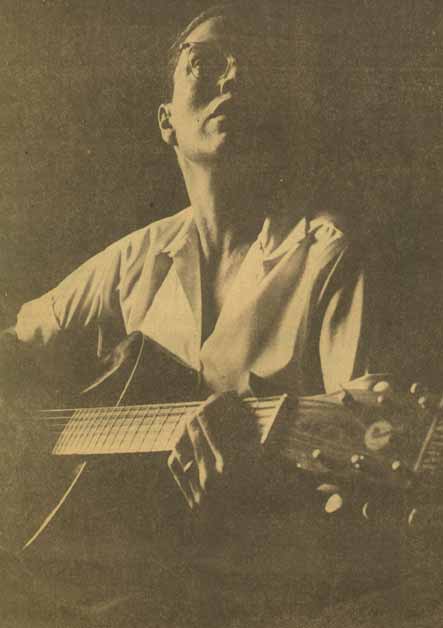

It was hot, even for a "hootenanny." Sweat rolled down the blond, crew-cut guitar player's face as he threw his head back and forced his voice up and out of its natural range. Beside him, glasses steamed, the mandolin player bent his head down, eyes closed. On the window seat sat a slender girl with a pony tail, holding a fiddle, waiting. In the small, book-lined room near Dinky Town she alone looked as cool as the great, white-plate moon that hung in the sky outside.

Three other members of the Folk Song Society of Minnesota entered the room where the "hootenanny," an informal gathering, was being held. Two of them opened instrument cases and began quietly adjusting pegs and strings. The third, a solemn, bespectacled man, flipped through the pages of a Library of Congress collection of lyrics.

The two players strummed out the last lick of Will the Weaver

and

sat down, handkerchiefs mopping their brows. The girl with the pony

tail, Mrs. Elizabeth Williams, tuned her

fiddle and in a flat voice almost devoid of emotion, began to sing

Barbry Allen.

And the only words she said to him:

Young man, I see you're dying.

Then four of the players -- Lyle Lofgren, mandolin, and Louis (Bud)

Claeson, guitar, the two who had sung Will the Weaver, and the

husband-and-wife team, Ann and Bill Bushnell, she on guitar and he on

banjo -- stood in a semicircle and swung right out into I'll Roll

in

My

Sweet Baby's Arms, a fast, "break-down" mountain tune with

humorous,

satirical verses.

Now where was you last Friday night,

While I was locked up in jail;

Walking the streets with another man,

Wouldn't even go my bail.

|

While Bushnell, an agriculture department plant physiologist in St. Paul, and his wife stepped out for a breath of air, Lofgren, the society's president; Claeson, its secretary-treasurer, and Dave Williams, who acts as the group's archivist and lyric collector, discussed the aims and objectives of the society.

"First, though," said Lofgren, a 25-year-old graduate student in physics at the University of Minnesota, "let me tell you about Will the Weaver. It will sort of set the stage. It's a British broadside -- that's a song, poem or political essay, printed on one side of a single sheet of paper -- as sung in the American mountains in the east. Broadsides began coming over here in the 17th century, and many of our songs are based on them. Our earliest folk music came from Scottish, Irish and English songs and these were fused together with local and regional ideas and playing techniques."

He went on to explain that the society got its formal start May 13 at a "hootenanny" at the university. "The 'U' wanted American folk music represented at their creative arts festival. We had been thinking for some months of forming a group, so we did right then."

"As soon as our charter man (23-year-old Claeson, a June graduate of the university law school) passes his bar exam," Williams said, "we'll get a charter and incorporate."

Williams, 28, is a philosophy major and management analyst at the university, and was one of those most responsible for bringing the society's members together. "We have about 20 performing members so far," Williams added, "and as soon as the summer's over we'll plan regular meetings. We also want to bring professionals in and hold performances of our own."

Williams and his 26-year-old wife are graduates of Reed college, Portland, Ore., and trace their interest in folk and traditional music to student days when they first heard the three-volume Anthology of American Folk Music, a series of recordings made in the 1920s and 30s that has become a classic.

"We're going in two directions," Williams said, "the academic -- tape recording and collecting songs -- and performing. Eventually we hope to promote a course at the university in folk songs and music."

Minnesota, Williams went on, is an "uncollected state." The Library of Congress, he added, has indexed only two folk songs from this state. "If we can complete an ethnographic survey of the state this summer," he said, "the Library of Congress has offered to provide funds to do research and collect folk music in Minnesota."

Mrs. Williams, returning from putting her two young sons, Mark, 4, and Kenneth, 2, to bed, caught the end of her husband's remarks. "But there are a few private collections in the state," she said, "and we're trying to track them down."

Williams nodded and continued: "The Library of Congress would like to see the university become an archive for folk music. It's going to be quite a problem, though, with all the different languages in this state. And one area that badly needs collecting are the songs of the north woods lumberjacks."

Williams said that there has been a renaissance of interest in folk singing in recent years, especially among younger groups, but that out of it had come "a lot of bad and some good." "Some of the trios singing nowadays are debasing the music," he said bitterly. "they are taking it out of its element and popularizing it."

Making the point that many in the audience think the work of some current trios is the "real" thing, Lofgren said that the only way to keep folk music pure is to sing it the way it should be sung and to get the audience to appreciate it. "What some of these trios and groups are doing," Lofgren said, "is giving the audience sugared-up, artificially rowdy versions of the real thing. And that's what many audiences want to hear now when you say 'folk music'."

|

At that moment, a late-arrival joined the group. He was 16-year-old Harold Streeter, a student at Vocational high school and a demon on the banjo, guitar and fiddle. Streeter plays "bluegrass" style. This style of playing and approach is as recent as the 1930s. The songs that are played mostly are without lyrics. The melody is picked out with three fingers on the banjo and the faster it is played the better.

Streeter sat down with the rest and out of the discussion, with everyone chipping in an idea here and there, came this picture: There is no "American folk music" as such. Folk music there is, but it's personalized, local, regional, the music of the north, the south, Massachusetts, Kentucky, the Negro, the chain gang, the depression. When words and tunes are known the country over -- for example, Barbry Allen, On the Top of Old Smoky -- the emphasis is on the individual performance, the artistry of technique.

It's not all "old" music. Much of it has been written in recent decades and some still is being written. It was live music in the 19th century and it still is live music in 1961. The newest aspect about it is the documentation, recording and collecting. Much of this was done during the depression under programs such as the federal writers project, the WPA, the farm security administration. The Library of Congress is the great storehouse of American folk songs and music. Among the most notable of collectors have been John A. and Alan Lomax, Cecil J. Sharp and Francis James Child. Were it not for these men much of the best of folk music in America would have been lost long ago.

The depression gave birth to songs that served a purpose like the

daily newspaper. There were songs of protest, songs of comment.

The other day my paper came, I sat and scratched my head,

While turning through the pages, boys, here is what I read:

The Blue Eagle it is ailing, the little writer said,

But when he finished writing, the Eagle he was dead.

And there were the Breadline Blues, How Can a Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live? Keep Moving, Join the CIO, The Loveless CCC.

|

Folk music is something filled with personal connections, songs passed on from father to son, sister to daughter, music heard in the mountains and on the plains as families and friends gathered for corn shucking and quilting bees. The instruments are the banjo, guitar, mandolin, autoharp, fiddle. Styles are as varied as the players. Some pick the banjo with two fingers, alternating between thumb and index finger. Others use a later style introduced by the great Earl Scruggs, who uses three fingers.

Instruments are tuned and retuned, often for each tune. The fiddle is played on double strings, sometimes retuned to get more chord strings.

Folk singing in America has its heroes -- Scruggs and the late Uncle

Dave Macon, who died at the age of 92 in 1954, among many others.

Macon, the "Dixie Dew Drop," was born in Tennessee. Many of the

songs he learned before 1900 from workers on the levee and along the

Mississippi were recorded among the 100 or so titles he cut between

1923 and 1938. His description of life on the chain gang in Way

Down the Old

Plank

Road is one of the most characteristic of a number of songs he

recorded. It also contains verses that are widely known folk-lyric

elements and that are found in other songs in other parts of the

country. Macon recorded Plank Road in 1926. It opens something

like

this:

Rather in Richmond with hail and rain,

Than Georgia wearing ball and chain ...

My wife she died on Friday night,

Saturday she was buried.

Sunday was my courtin' day

Monday I got married ...

With these phrases tagging along at the end: Eighteen pounds of meat

a week, whisky to sell; can a young man stay

at home, the girls look so well; won't get drunk no more on the old

plank road.

"That's about as exuberant as folk singing ever gets," Lofgren said, after the group had whipped in and out of a fast and spirited performance. "As you can see, it's also another example of a song with disconnected verses."

And so the "hootenanny" went, from one song to another, far into the hot, steamy night.