|

Over the years, I've learned to look for counter-intuitive situations, and I found one for this trip: at least for a few weeks, it's a lot cheaper to fly to Las Vegas and rent a car than to fly directly to Los Angeles, even though LA is 200 miles further from Minneapolis. The plane was packed with noisy people looking forward to winning big and not having to work for the rest of their lives. We ate at a cheap buffet in one of the casinos, each lost a quarter to the slot machine, picked up our rental car, and headed for southern California. Victorville: On I-5 just outside Victorville, CA, Liz yelled "turn around," which is a fairly common command on our trips. I looked to the right in time to catch a glimpse of homemade trees festooned with green wine bottles that glowed in the sun. We turned around at the next exit and discovered Miles Mahan's Hula-ville Museum. Miles is 96, and his mind wanders a little, but he says his museum and mini-golf course (with green wine bottles for hazards, of course) has been on Jane Pauly's show, as well as Johnny Carson's. He sold us his book of poems, which includes the justification for the bottle trees: On a mound bottles ya see There's a lot of poetry in his book. He says the hardest part is to get the lines to come out even, which seems to me an excellent explanation of why you need craft to produce art. Miles said his father was a car dealer in Alaska, but when I questioned further, it turned out he had said "card dealer." His mother died when he was young, and he was raised by a grandmother. He hoboed during the 1930s, riding the blinds, but never the rods. I asked what blinds were, but didn't understand his description. It seemed to involve the back of the coal tender in some way. There was room for three to sit abreast on the blinds. They looped their belts together and the ones on the end also looped their belts through brackets. That way, all three could sleep sitting up. He quit hoboing in 1937 and became a carnival weight guesser, mainly in the west. He knew of Minnesota only because other carneys had talked of the State Fair in St. Paul. Weight guessing is a hands-on art. You need to feel at least the customer's thigh while diverting their attention with patter. He demonstrated the patter on me (I didn't notice the thigh squeeze) and said "250 and one-half pounds." That's within one pound of my present weight. In addition to bottles, there's an old life-sized

wooden Hula Girl from a Los Angeles nightclub, an old

hotel sign, wagon wheels, the floor of a burnt-up

trailer—a carefully arranged collection of society's

jetsam. Despite the rhyming signs painted all around,

there's no attempt at interpretation. In this way, Miles

is post-post-modern. If I understand his meaning

correctly, he's saying, One of the signs on his mini-golf course, here in the middle of the desert, reads, "During thunder/electrical storm, discontinue play and return to clubhouse." Good advice, seldom followed. There is, of course, no clubhouse. Miles is another example that, to live what Liz calls an Authentic Life, you have to be eccentric. It also helps to have an infrastructure. While we were there, a Meals-On-Wheels volunteer drove up with lunch for Miles. [Note added 2010: Miles, of course, is long gone, but part of his collection is still on view at the Route 66 Museum in Victorville.]

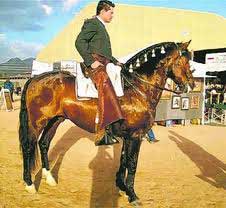

Ramona: We drove on to Ramona, a town in the

desert northwest of San Diego, to spend some quality

time with Eloise, an old friend, who, like Liz, is

horse-crazy. Eloise used to ride and train retired

Thoroughbreds for a second career as show horses. Her

current craze is for Iberian horses, specifically

Portugese Lusitanos. Thoroughbreds are long, lanky, and

built for speed, but Iberian horses (Andalusians and

Lusitanos) are compact, elegant, and agile: horses bred

for bullfighting and to be ridden by Hispanic royalty.

Eloise keeps her horses at the same stable as Budd

Boetticher, who directed a number of Randolph Scott

movies in the 1950s. Budd once trained in Mexico to be a

bullfighter, and made a movie called The Bullfighter

and the Lady. He now buys and sells Andalusian and

Lusitano horses, and has built a bullring at the stable.

Well, he doesn't fight real bulls -- just a wheelbarrow

with horns that an assistant wheels around while Budd's

horses do their fancy footwork. This is Portuguese

bullfighting, where the bull is not killed. Good thing,

too, as otherwise one would go broke buying

wheelbarrows. In addition to riding horses, Budd wants very badly to make another movie, although he's long been out of touch with the Hollywood people who can make things happen. He has a script called (as I recall) A Horse for Mr. Barnum, about some cowboys who go to Europe to find horses for P.T. Barnum. He gave us the script to read overnight. It would indeed make a terrific movie, but he must be desperate to have strangers read the script. I suppose that, since Liz is horse-crazy, there's always the possibility that we're multi-millionaires who'd just love to back his movie. He also loaned us a VHS copy of The Bullfighter and the Lady, as well as a self-made documentary about Budd as a trainer of bullfighting horses. We complimented him on his movies, his script, and his horses, but didn't buy any of them. [Note added 2010: Budd Boetticher died in 2001, at age 85. According to Wikipedia, he never found anyone to make his Barnum movie.] Tijuana: Eloise is training a couple of horses for Phil, who sells computers. He also practices martial arts and collects Indonesian Kris swords. Eloise said we had to go to Tijuana to see Rudolfo ride, as she had contacted him to arrange a Saturday demonstration in Tijuana. Phil volunteered to drive us all in his bright red Dodge Stealth, so on Saturday, Eloise, Phil, his wife Jill, Liz and I all fit into the Stealth and headed for the border. Eloise says that Rudolfo is now the greatest rider in the world since Nuño Olivera of Portugal died. Rudolfo trains Andalusian horses at Agua Caliente racetrack, which is somewhere in Tijuana. No one in the car had any idea where Agua Caliente was, so we explored much of Tijuana looking for it. Also (typical for gringos in southern California), no one had any idea how to say "where is ...?" in Spanish. As part of the search, we drove for a mile or so along the corrugated metal fence that separates Mexico from the U.S. One or two thousand Mexican men were lined up along the wall, waiting for dark to cross the open area beyond Tijuana into the U.S. About a quarter-mile into America, a small 4-wheel drive vehicle with 2 men in it sat on a small hilltop, representing the U.S. INS patrol. Mexican labor is badly needed to harvest the crops in California so the rest of us can buy what we want at the supermarket, but the INS intends to uphold the law, albeit ineffectively, given how badly they're outnumbered.

We finally found Agua Caliente, which is owned by a Mexican millionaire who reportedly also owns 200 Andalusian horses. We drove around to the backstretch, where the barns are. They're fortunately numbered, and we found Rudolfo's barn. Rudolfo, unfortunately, was not there, because he didn't know he was supposed to ride for us, said a very friendly girl who works for him. But they've sent for him, and he'll be here shortly. Meanwhile, they led out some Andalusian horses for us to look at, priced at $25,000, $30,000, and one stallion, a bargain at $231 K. According to Eloise, the main problem with Mexican Andalusian horses is that they usually have counterfeit papers. Meanwhile, the stadium across the way was collecting a sparse crowd to bet on the greyhound races to be held later in the day. Evidently no horse races were taking place. I got bored with the horses, so I wandered along a path bordering the racetrack. I stopped to watch a man leading a greyhound out of one of the barns. He took the dog around to the side and commanded him to sit. While the dog looked soulfully at him, the man took a revolver out of his pocket and shot the dog dead — evidently the Tijuana dog retirement program. I was only too happy to go back and watch the horses, where the girl told us that Rudolfo has arrived, and is right now dressing to ride for us. All the horses that were for sale had been shown, so we had nothing to do but stand around and wait for Rudolfo. After a couple of hours, a wind had picked up and it was starting to get cold. The dog races had not yet started, and the crowd didn't seem to have grown any, either. Finally, the girl returned to tell us it was all a false alarm: the men sent to find Rudolfo couldn't find him after all. When we asked why she had told us he was here, her ability to speak English deteriorated greatly, but I think she apologized to us in Spanish. Before we left, I walked back to check on the dog. He was still dead, laying by the side of the building.

It took about 2 hours to get back into California.

During the wait at the border, dozens of vendors walked

up and down the lines of cars, trying to sell us cheap

goods: pots, serapes, glass boats, and ceramic horses.

We didn't buy anything, but it was dark by the time we

hit I-5 heading for San Diego. I-5 has road signs like

the deer crossing signs in other states, but these show

a man, woman and child running across the road — wetback

crossing signs. We stopped in San Diego for dinner, and Phil told us Kris sword stories. He keeps his collection in a special room, where Jill is not allowed. Once, while Phil was out selling computers, Jill entered the forbidden room. At once the swords all began to jangle on the wall, so she got scared, ran out, and has never entered again. Jill, who is quiet anyway, did not confirm nor deny the story. I didn't want to ruin the ambience by suggesting that the swords may have been jangling due to a small earthquake. The flight back to Minneapolis from Las Vegas was also packed, but we were able to get some rest, because the crowd was subdued. The fun was over and the money all gone. Everyone aboard was faced with having to return to dull jobs for the rest of their lives. We were the only ones who were happy: rich adventure and cheap air fare. [Note added August, 1993: |