|

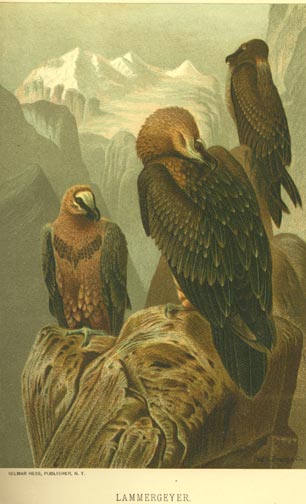

[Note: The title is based on a school report our son, Mark, prepared when he was in about 2nd grade. Each page featured a crayon drawing of a common garden bird, with a recurring title that required only the substitution of the bird's name: The blue jay is one of our prettiest birds was followed by The cardinal is one of our prettiest birds. Of course, being a grownup, I had to add a whole bunch of impressive references. You don't need to look at the footnotes while reading this -- they won't tell you anything new.]  (Lammergeyer illustration from Wood, Animate Creation3) Peter Matthiessen had been really hoping to see a Snow Leopard1. He'd made a wind shelter and lookout, just at snowline, facing north over the Kanju (Black) River Canyon, Inner Dolpo, Nepal. He had a good view of the caves and ravines across the canyon, in case a Blue Sheep should get killed by a Snow Leopard. The leopard chews on a carcass for days, so his best hope for seeing one lay in looking for a gathering of Griffins, Ravens, and Lammergeier. The Lammergeier (Dutch for Lamb Vulture), or, in English, Lammergeyer, is a gigantic bird, with a wingspan up to 9 feet. It has narrow, angled wings and a long, diamond-shaped tail2. The British call the Lammergeyer the Bearded Vulture because of long bristly hairs that grow out of the bird's nostrils and underbill3. It lives in remote mountains of Spain, Sicily, Ethiopia, Turkey, and the Himalayas. It has been seen at 25,000 feet4, gliding serenely on the incessant winds blowing up the sheer gray crags, or riding the invisible lee waves in the air just downwind of a peak. The Lammergeyer, like all birds, needs calcium to make eggshells. It gets this by breaking the bones of large mammals against rocks. Its Spanish name, Quebranta Huesons5 and Latin name, Ossifragus6, both mean bone-breaker. Leslie Brown7 says: It has dark upper wings and tail, with a light buff-colored head2. A prominent black eyepatch extends forward to join the dark beard in a harmonious manner. It has light underparts, apparently too light. Not content to wait for evolution, it squats in fine red dust, coloring its breast orange7. Grossman8 says there is variable brown spotting on the chest, but I prefer the illustration given in Wood3 (shown above), where I first ran across a description of the bird. The artist rendered the chest spotting in the outline of a soaring Lammergeyer flying the other direction, pointing towards the rear of the bird. Perhaps it is trying to give the impression it has already flown by. But, back to Peter: he's sitting near the edge of the cliff,

looking for birds

of prey, and feeling part of the mountain (much of the book is devoted

to his search for Buddhist meaning to life). Suddenly1, Look out, Peter! If you had read up on your Lammergeyers,

you'd know that this guy is dangerous. For instance, Nicolai9

says: It also likes turtles. It scoops one up in its talons and performs the old bone trick, splitting the turtle's shell in several pieces. Hausman10 says that Pliny the Younger11 said that it seems the poet Aeschylus12 made the mistake of going to see the Oracle. The Oracle said, "Aeschylus, on such-and-such a day, you're gonna die when a house falls on your head." So what would you do in his situation? That night, he didn't sleep, and went outside long before midnight. He stayed outside all day. The sun, high overhead, flattened all perception as he walked in a rocky area well away from town. Although the turtle had felt himself snatched upwards, and the earth was fast falling away from him, he was not alarmed. His ilk had been around for at least 170 million years13, because he always carried his house with him. The Lammergeyer, looking for a suitable rock for turtle shucking, saw Aeschylus's bald head and dove for it. Nobody beats out Oracles. That's why you shouldn't consult them. But if the Lammergeyer is a comic in the manner of Ghede, the

Voodoo guardian of the cemetary14, it also shares with Ghede

the

capability of being peevish and petulant15. For example,

Brown16 tells

a degraded version of the Aeschylus story: Golden Eagles, or Thunder Eagles, as some American Indians

call them, had been following Peter for weeks. After he and his porters

broke camp, they and the Lammergeyers would come by and pick through

the refuse, scratching up and eating the feces lightly covered with

snow17. Earlier, Peter wrote in his diary18, The Ancients said that living things are composed of a mixture of four elements: earth, water, air, and fire. And to one of these elements we must return. Earth is the commonest of these, although many choose fire. Some want cremation followed by the sprinkling of ashes on land or sea, in an attempt to return to two elements with one shot. When I was very young, during WWII, I saw a newsreel film of a mass burial off a US battleship that had just barely survived a Japanese air attack. Five coffins were lined up, a perfunctory shot fired, and down into the sea they slid. To be followed by five more, on and on. We think of ourselves as being at the apex of the food chain, but what of the scavengers in the earth and under the sea who are waiting for breakfast? And what of the fourth element, air? Peter tells of a Tibetan custom, called air burial19. The body of the deceased is dismembered and set out on a wild crag for the Lammergeyer and Thunder Eagle. Later, the relatives go to the ossuary to collect the fragmented bones of the departed. These are ground into a powder and mixed with water into lumps of dough. The dough is set out for the garden birds that used to hang around near the house when the person was alive. A devout Tibetan Buddhist does not call the undertaker, but the overtaker. |