The Civil War era had two song writers, both of them famous for great melodies and heartfelt lyrics. The South had Stephen Foster (who was actually a Northerner, but who wrote almost entirely about Southern life), while the North had Henry Clay Work. In spite of the hostilities, northerners sang Foster songs while southerners sang Work songs. You can still hear southern Bluegrass bands perform Work's works -- two examples are My Grandfather's Clock and Kingdom Coming -- and even occasional instrumental versions of his Marching Through Georgia. One of his other songs, The Ship That Never Returned, told the generic story of a sea voyage and all the people that left but were never heard from again. The story was mainly carried by a great tune, so it was popular throughout the last half of the nineteenth century.

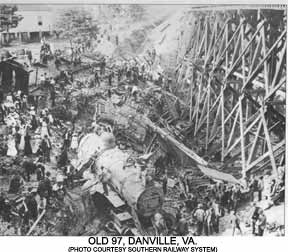

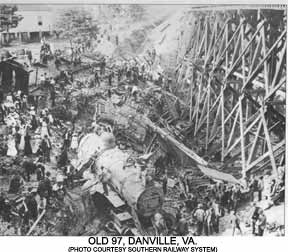

In 1902, the Southern Railroad signed a contract with the U.S.

Government

to provide service between Washington and Atlanta with a mail-only

express

train, designated #97. They optimistically guaranteed on-time delivery,

even though the roadbed wasn't in all that good condition. The train

tended

to run late, so it wasn't unusual that, when rookie engineer Joseph

(Steve)

Broady took over in Monroe, Virginia, on September 27, 1903, he was

already

forty-seven minutes in the hole. Going downgrade from Lynchburg, he

made

up time by "whittling," picking up speed on the straight-aways

and braking hard on the turns, just like a Minnesotan who first

encounters

a downgrade in the Rocky Mountains. Like the Minnesotan, his brakes

gave

out at the bottom of the hill, and he was evidently doing ninety when

the

train careened around the last turn before the trestle at Danville. A

famous

photo shows the engine and associated wreckage in the Dan River gorge,

about

forty feet too far to the right, and about seventy-five feet too low,

to

make it across. Counting the engineer and the fireman, eight people

died,

which seems like small potatoes compared with modern wrecks.

Still, a witness (three different people eventually claimed credit) wrote these verses shortly after the accident. You can tell it was a prompt effort by the accuracy and specificity of the details. Legend says that the poem was a hit in the Danville barber shop, where someone suggested setting it to the tune of Work's Ship song (it wasn't much of a stretch, since modem times had already transmogrified it to The Train That Never Returned). Henry Whitter, a Virginia musician with a record contract, picked up the song and recorded it in 1923. Vernon Dalhart, a pop singer who developed a twang to become the first citybilly, heard that disk and covered it for Victor in 1924. That became the first of the "hillbilly" offerings to attract city buyers, and was the first million-selling record in any genre. It was so popular that Broady's widow made a public statement that she had not spoken harsh words to her true loving husband*. In addition, of course, the competing authors came out of the woodwork with the first set of copyright lawsuits in the record industry. All the suits were overturned on appeal, so you have a choice of three names for the original genuine author: Graves, Nowell, or Lowey. It doesn't matter to me, because I regard the song as a good example of how the Tradition works. Almost anyone who heard of the wreck and who had a decent sense of traditional rhythm and rhyme could have written it (maybe it was Kilroy). In fact, Justus Begley of Hazard, KY sang a completely different train wreck story to the same war-horse tune (The Wreck On The Somerset Road, where some vandals loosened the rails). If, however, you hear someone sing the third verse of "97" and the engineer loses his "average" instead of his "air brakes," you can be confident the ultimate source is the Dalhart recording, since Vernon, for all his mountain twang, had a hard time understanding what those hill folk were singing.

The words given here are a combination of several versions I've heard over the years. If it's not an accurate reconstruction of what the original verses were, it's what they should have been. I got the train wreck story from the notes to the Blue Ridge Institute album BRI 004 Virginia Traditions: Native Virginia Ballads and an article on the wreck that Bruce Jaeger reprinted in the May 1992 Inside Bluegrass. Norm Cohen wrote a book, Long Steel Rail, that reportedly also includes the Old 97 story, but my local library doesn't have a copy.

There are many dozen train wreck songs. I wonder why no one writes about airplane crashes?

They gave him his orders down at Monroe, Virginia,

Saying, "Steve, you're way behind time;

This is not 38, but it's Old 97,

You must set her into Spencer on time."

He turned around, saying to his black, greasy fireman,

"Just heave in a little more coal,

And when we reach that White Oak Mountain,

You just watch Old 97 roll."

It's a mighty rough road from Lynchburg to Danville,

And Lima's on a three-mile grade;

It was on that grade that he lost his air brakes,

You can see what a jump he made.

He was going down grade, doing ninety miles an hour,

When his whistle began to scream;

They found him in the wreck, with his hand on the throttle.

He was scalded to death by the steam.

A message arrived at Washington Station,

And this is what it read:

Those two brave men who pulled Old 97

Are lying in Danville, dead."

Oh, ladies, you must take warning,

From this time on and learn:

Never speak harsh words to your true loving husband,

He may leave you and never return.

This song is Laws G2, and Laws lists sixteen different versions,

from

Arkansas, Colorado, Kentucky, Missouri, New York, North Carolina,

Tennesee,

and Virginia.

Long Steel Rail: The Railroad in

American Folksong, by Norm Cohen. University of Illinois

Press, 2nd edition, 2000.

Scalded to Death by the Steam,

by Katie Letcher Lyle. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1991.

In addition to the references to Long Steel Rail, see the article The Wreck of Old 97, by Freeman H. Hubbard, published in Railroad Avenue.

Modern versions of the song continue to be found, but increasingly they are contaminated by the Dalhart version. That the song is not by any of the claimed authors is proved, e.g., by the much longer version printed by Randolph (his #683).

The Ship That Never Returned is Laws D27, and Laws has six references, from Kentucky, Missouri, North Carolina, and Tennessee. Laws's notes on D27 also list versions of The Train That Never Returned.

Return to the Remembering the Old Songs page.