|

Gustav Lofgren (R.G.) Smith

(Jan. 6 or June 1, 1870-Nov. 26 or 28, 1951) =

Wilhelmina Josephina (Minnie) Smith (July 31, 1871-Apr.

18, 1965) in 1894

Children:

Wallace Paul Victor Smith (May

2, 1895-May 17 or 21, 1963) = Mildred Vestlund (?-Sept.

18, 1927) on Aug. 24, 1927

Wallace Paul Victor Smith

(1895-1963) = Evelyn Butler(?-?)

Patricia

May Smith (1941-) = Vincent Carter (1938-) in 1962

Kirk Wallace Carter (1963-)

Kraig Vincent Carter (1963-)

Patricia

May Smith (1941-) = Glenn Johnson (1949-) in 1973

Jayme Johnson (1976-)

Lucia

Alexis Smith (1949-) = Stephen Gainer (?-) in 1980

Jarred Gainer (1989-)

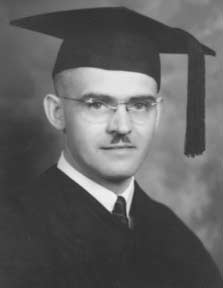

[Wallace was a professor of history at Fresno State

University, and wrote several books on the history of

the San Joaquin Valley. His first wife, Mildred,

contracted polio on their honeymoon and died only 3

weeks after their marriage.]

Raymond Theodor Smith (Apr.

12, 1897-Dec. 6, 1980) = Edith Swenson (Jan. 31, 1904-?)

in 1930

No

children.

[Ray worked for the telephone company, and visited

Minnesota several times. He even took home movies and

had a wire recorder we could speak into!]

Mildred Pauline Smith (Mar.

14, 1900-1989) = Halfre Bohleen (1894-1983) in 1929

Gladys Ruth

Bohleen (May 14, 1932-) = Robert Rose (1931-) in 1963

Coleen Rose (1958-) (from Robert's previous

marriage)

Rhiannon (1978-)

Douglas Rose (1964-)

Alice Vilhelmina Smith (Nov.

15, 1901-1999)

Ethel Emilia Smith (Mar. 9,

1903-1995) = David Stanley Kent (1903-1940) in 1936

Jon Stanley

Kent (Apr. 3, 1940-) = Patricia Ann McCarroll (1942-) in

1962

Robert David Kent (1963-)

Michael Edward Kent

(1975-)

R.G. also worked with C.A. on the Wyoming spur line.

Here is a professional photograph of C.A., R.G., and

Fred, along with Mr. Westlund, on a handcar.

ON THE WYOMING (MINNESOTA)

SPUR LINE, 1880s

FRONT ROW (L-R): MR. WESTLUND(?), C.A. LOFGREN.

BACK ROW: R.G. & FRED LOFGREN

|

Minnie Smith was the daughter of a

pioneer Swedish immigrant, John Anderson (1825-1888),

who was born in Sörby, Linköping, Sweden, came

to America in 1851, and cleared 160 acres on a peninsula

on what is now North Center Lake of the Chisago Lakes.

When he applied for citizenship in 1852, he changed his

name to John Smith, because it sounded more exotic than

Anderson. Minnie was worried that the name would die

out, so, when they married, she convinced R.G. to change

his name to R.G. Smith. Ironically, the daughter who

stayed on the farm, Anna Smith, later married P.J.

Anderson, who evidently didn't go for the

take-your-wife's-name idea, so the land reverted to

Anderson land. (I learned this quite by accident from

Mark Anderson, a descendent of Anna Smith Anderson, who

I met at a party given by mutual friends). After

marriage, R.G. continued to work on the railroad for 12

years. They then moved to Kingsburg, California (1906),

where they began growing grapes for raisins.

In 2007, Gladys Bohleen Rose and her husband, Bob,

visited us in Minnesota. She added some information to

the above account. There was considerable friction

between R.G. and C.A. Lofgren. (Arvid Lofgren told of an

example: when straightening rails, C.A., as section

boss, decided when the rail was straight. R.G. would

then sight down the rails to decide for himself if C.A.

was right.) They all lived in the section house, with

C.A.'s wife Augusta cooking for the crew. Augusta would

open all mail addressed to Lofgren, no matter if it was

addressed to C.A. or R.G. According to Gladys, that was

the main reason for R.G. changing his name to Smith. So

it wasn't to honor Minnie Smith after all. And here I've

always thought, "at least there was one romantic in the

family."

In addition to the friction with C.A., R.G. didn't like

the cold wather in Minnesota, so when a former pastor at

the Lindstrom church wrote back to say how wonderful it

was in California, R.G. and Minnie decided to head for

the promised land. They arrived in San Francisco only a

week or two after the big earthquake, so they headed for

Kingsburg, which already was a thriving Scandinavian

community (even today, the water tower has been modified

to look like a Swedish coffee pot).

In response to the first edition of this history, Jon

Kent of Santa Barbara, California sent the following

information about his relationship with R.G.:

My dad died in 1940, just 6 weeks before I was born,

so mom moved back to the farm in Kingsburg, where I

grew up with my grandparents, R.G. and Minnie, and my

aunt Alice. Wallace also lived there for a time so we

had a house full of teachers. I recall driving the

team of horses, then later tractors. I still have the

hand pump that we used for drinking water. Uncle Ray

taught me so much and I followed in his footsteps in

driving school buses and tour buses for the National

Parks while in college. I have all of his old movies

you mentioned. Pat and I met while students at San

Jose State University. She was born in Juliaca, Peru,

where her dad was a mining engineer. Both parents were

from North Dakota, but her mom was born in Nova

Scotia, and may be a distant relative of mine! (well,

we are all related somehow, aren't we!). My father's

side of the family came to Nova Scotia from Scotland

and I have quite a family history of those wild

folks--they were all peasants too!

R.G. SMITH & FAMILY, 1919

(?)

BACK ROW (L-R): ETHEL, WALLACE, RAY, ALICE

FRONT ROW: R.G., MILDRED, MINNIE

|

In 1951, R.G. was burning trash in his yard when his

clothes caught fire, and he died from the burns. Five

years later, Wallace wrote this detailed letter to

Esther Lofgren Alvin, describing the agony of his death:

December 12, 1956

Dear Esther:

I feel like writing a few words to you tonight. I

think about your mother and my father and the other

persons who have passed out of our lives. You lost a

husband a long time ago, and I buried my first wife. I

often wonder what life is all about.

During the hurly-burly of our father's death I was

so busy that I do not now know whether we sent a copy

of the article about him which appeared in the Fresno

Bee or not. I do remember that I sent an article to

the Chisago County Press together with a request to

Mr. Fred Feske of Lindstrom, a son-in-law of Eddie

Andrews, and a great friend of my Dad, both Feske

& Andrews, that he see that the article be

printed. It was not! Just a short notice! I resented

this, but Norelius, the editor, told Feske, that my

Dad had been away from Lindstrom and Center City so

long that no one would remember him.

Is not life strange. My Dad had coffee with my

Mother, Ethel, and Jon at 10:30. Alice was sick with

the influenza, and was in bed upstairs. It was a

Saturday. Dad then said I am going out to burn some

rubbish, a pile about the size of a small package, not

more than an ordinary person could have carried away

in his two hands. He had bought a new pair of pants

and did not want to get them soiled, so he put on an

old home-made apron which he had made of gunny-sacks.

These sacks had been secured when he had ordered twine

which is used to tie up the canes on the Thompson

Seedless vines. In order to prevent the twine from

rotting, these sacks are treated with an inflammable

emulsion, the kind that does not flame up, but which

burns stubbornly and will not go out easily. It was

blowing slightly that day and as he turned the flames

from the small fire caught hold of his apron without

his knowing it and slowly burned up toward his waist

from the rear. When he felt the heat, he hurriedly

tried to untie the rope which he used to keep his

apron in place, and perhaps due to nervousness, or

because he had tied it too tightly he could not

unloosen it. He had no knife to cut it with and the

fire kept getting hotter, so he cried for help. He

could not roll on the ground to put out the fire, as

the ground was hard, and would not help much, and so

he ran toward the tank-house where Ethel was washing

clothes. Ethel had taken a course in first-aid, and

knew what to do. She put wet wash down in front to

prevent the fire reaching his genital organs, and over

his face. These portions of his anatomy were saved.

But she told me that the wet wash seemed unable to put

out the fire forthwith on his trousers, which burned

away entirely as did his underwear. He was not burned

above the waist, but everything below his belt,

excepting his genitals, appeared to me to look like

raw beef-steak. Oil seemed to exude from all portions

of his lower anatomy when I helped the nurse, Mrs.

Arthur Davidson, change his bandages one morning about

2 A.M. I often went down at night, and stayed until

the wee, small hours of the morning--I had to teach at

Fresno during the day—but kept going down to Kingsburg

at night. I was rather fatigued when it was all

over--he lived for 12 days after the accident--but I

did what I could. A young Army doctor, recently

discharged from the Service, and just then located at

Kingsburg, had the case at the Kingsburg hospital. One

of my neighbors here at Fresno is a retired doctor, a

specialist, and he went with me to see my Dad. He

talked to the young doctor and assured me that he knew

what he was doing, had had much experience with burned

men in the war, and hence no one could do more than he

was doing. So I could then tell my Mother that all was

being done to save Dad. This made her feel better.

My Dad had said, when he went out after 10:30, that

Mother and Ethel should come out at 11 o'clock, and

they would see how nicely he had cleaned up things.

They came out sooner than that, but not with the

original hopes and promises. When my Mother heard the

commotion, she ran out and turned the hose on. It

never fails, the hose was not attached to the facet,

and by the time she had time to hook it in place,

Ethel had killed the fire with the wet wash. It had

all been a matter of seconds. How easy it is to say

that if I had been there with a knife to cut the belt

that held up his apron, or if the hose had been handy

to squirt water on the fire and apron, if-if-if-if-if

he had not tried to burn the rubbish, but had carried

it into the field, et cetera. Life is like that. I try

to cheer my Mother by telling her that his days were

numbered. Had he not lost his life in the fire, he

would soon have passed away due to hardening of his

arteries, the doctor said so, or he might have had an

accident. He still drove his car, and he drove it too

fast--supposing he had had an accident, and had

inadvertently killed someone? The way it was, he died

honorably, and all were sorry to hear about it.

One thing makes me happy, and I am sure you will

appreciate this. He had always been religious, and I

wondered how his religion would hold when he was hurt,

in agony, and no doubt realizing that it was all over.

The Army doctor is a young man of a religious

background, a Mennonite, somewhat like the old-time

Quakers, and he told me he had never met a patient who

was more cheerful under pain. When I went to see my

Dad he kidded me the first time; he said: "Wallie, the

trouble with me is that I don't know how to wear

skirts." He also made a wonderful impression on the

nurses--young and old. One of the older nurses told

him one morning: "You will soon be home, and then you

can celebrate Christmas with your family." He

answered: "You are all so nice to me, and I appreciate

it, but I know better." He never let on to any of

us—his family—but he apparently knew the end was near.

I talked to him about 3 o'clock one morning--Mrs.

Davidson was there--and I patted his shoulder and I

said: "I hope you will get well." He looked at me but

said nothing. Then I added: "I have always admired

you, and been proud of you, and whatever happens, I

want you to know that." He said very calmly: "Well, I

always thought you did." There were no tears, or silly

weeping. We talked man to man, and I told my Mother

about it afterwards. She felt good about it, but sorry

that she had had no last words with him. She was

always taken to see him during the day, when he was

dopey with drugs--I went there during the night when

the drugs had worn off, and he was about to get his

new dosage, so I saw him when he was at his best

mentally.

Had he shown fear of death, anger, or crankiness, I

would have grieved over it, but all concerned, nurses

and they were all, with the exception of one nurse,

good church members and Christians. The one nurse, a

pretty girl, who had no faith, told me that if

religion does that to a man I want to investigate it.

"He dies the way I wish I could, when my time comes!"

One night he asked the elderly nurse on duty—a good

Baptist—to sing Trygarre kan ingen vara, än

Gud's lilla barna skara—and he tried hard to

follow her. He could not sing, as you know, but she

was visibly affected by it all. I do not spell Swedish

well, so no doubt I misspelled some of the foregoing

words.

Paul Lofgren, our cousin, came down to see Dad, and

the latter looked happy when he saw him; it was in the

PM and Dad was somewhat dopey from drugs, but he

called Paul by name, and told me afterwards: "Did you

know Paul is here; he is upstairs." There was no

upstairs, but he did know Paul had come.

According to the mortician and the flower shops, it

was the largest funeral in Kingsburg's history. It was

raining hard--really pouring--and so the crowd which

could not get into the mortuary really must have liked

him to stay out in the rain. Ethel's fellow teachers

from Fowler were there en masse; my fellow professors

from Fresno sent flowers; the words spoken by the two

clergymen were so unusual that one lady from

Fresno--her husband is a State official and she was at

one time a high school teacher--said she had never

heard anything like the beautiful tributes paid him.

The memories are sweet; he lived his religion and

when he was hurt unto death he never once whimpered.

When he was unconscious he moaned terribly, but the

doctor said this was due to internal agony which he

did not allow to show when conscious. I think often of

him when the holidays come, as he was buried on

December 1st.

One thing I resented. I had talked my Mother into

accepting the inevitable, when the nurses at the

hospital, no doubt meaning well, began to tell her Dad

would soon be home. We had Thanksgiving dinner at

Raymond's and Mother had just come from the hospital.

She said: "The nurses tell me Pa will be home for

Christmas." Then everybody began to talk in that

manner, and I finally burst out: "Will you please stop

tormenting a poor wife and mother? I have had her in a

frame of mind where she was willing to accept the

inevitable, and now you are working up false hopes. It

is cruel." I went down to the hospital later, and told

the nurses to cut it out. They did.

"It is appointed unto all men once to die." This I

know! I have seen friends and relatives die. I was not

present when my Dad died. The old Baptist nurse

maintains she suddenly heard the rustling of wings,

and then a soft sigh, and my Dad was dead. I do not

know about such, things. Perhaps there was such a

rustling; perhaps she imagined it; but she did testify

that no man could have talked more sweetly,

confidently, or eagerly about his faith in God and the

Hereafter than did my Dad when he was unconscious and

truly revealing himself.

Death is not the worst that can come to us. One

night I went to see a friend--I am glad he was not

around--I would have frightened him--and I cried as

hard as a little child who has stubbed his toe--from 2

until 4 o'clock in the morning--I then went home--and

have not done so since. No death was then imminent. I

buried a wife, a Dad, other friends--and I have shed

no tears at those times--one can control oneself--so I

don't think I am a baby, but sometimes the struggle

get tough, and for once I lost my self-control. No

doubt you have had those moments. Come and see us some

time. I would like to visit you-all. I love you very

much--Esther, Elmer, Paul--but who knows? Forgive this

long-winded epistolary effusion.

Wallie

|