| 17.

THIRD GENERATION (SWENSON):

(17.1) Maria (Maja) Olofsdotter

(1813-? ) = Gabriel Swensson (?-? ) in

1834 (?).

My mother Ida told me that her grandmother Maja Olofsdotter (although she didn't know her name; I got that from Alf Gunnarson) married Gabriel Swensson when she was 16 years old. (Information from Sweden says she was 21.) They had the four children listed. Ida called the oldest, who was a neighbor when she was growing up, Faster Lena (faster, an abbreviation for far's sister="father's sister"). Her name was pronounced LAY-nah, which sounds elegant compared to the American pronunciation, LEE-nah. About a year after Gabriel died, Maja married Sven Svensson. Ida told me that Sven had come to Finnerödja years earlier from a Swedish-speaking section of Finland. The reason why he came is lost to history, but whatever it was, it didn't work out, so he became a "handyman." His duties in the community included giving advice, writing letters for people, splinting broken bones, and snapping dislocated shoulders back in place. Some handyman! Again, a good story from the first edition ruined! The

genealogy

I received from Alf in Sweden indicates that Sven was from Finnerödja,

and his

family had lived there for generations. So who

was the Finnish handyman? Was it Gabriel Svensson? Or is there

confusion here because Sven Svensson's son was named Sven Svensson? Or

is the whole story a myth? I need to know, since I've attributed many

irrational acts to my Finnish heritage. [See the prolog

to this section for the Finnish connection. It goes back much further

than any of the Svennsons in this generation.]

In the winter they made charcoal for sale to merchants and

blacksmiths.

The charcoal was made in a kolmila (KOOL-meel-AH), a pit or

pile of

timber built in the summer, then covered with leaves, hay and earth.

The wood in the kolmila

had to be carefully tended for 3 days after

it was lit. You needed enough air to keep the fire burning, but not so

much that it burned up the charcoal. The charcoal maker slept in a

nearby kolarkoja

(KOH-lar-KOY-ah=charcoal hut), a small hut of sticks and covered

with earth. Inside was a fireplace for cooking and warmth, and along

the side an earthen sleeping bench covered with fresh evergreen boughs.

Boys often were sent to tend the kolmila. One winter

while tending the fires,

Olof froze all

his toes. Sven heated a chisel red hot and cut all the boy's toes off.

The hot chisel sealed the wounds, and he lived to come to America,

although Ida remembered that "Uncle Olof always walked kind of funny."

In 1877, Olof Gabrielsson, Carl Rundberg, and Carl Rundberg Jr. came to America, stopping in Michigan. Carl Jr. got a job in the mines, and was later killed in a mining accident. Olof and Carl Sr. bought land in Minnesota through a St. Paul land agency, and moved there. The 1888 plat map of Fish Lake township shows Olof Gabrielson owning 40 acres (location # 2) and Carl Ramberg (sic) owning 80 acres (location # 3). By 1879, the rest of the family, Lena Kaisa Rundberg and her children August, Edward, Oscar and Anna, were able to come to America. We visited Trehörning in

1984. It is now abandoned land, and all

the buildings are gone. (17.3) Karl Gustav

Karlsson (1832-1889) = (17.4)

Gustafwa

Jonsdotter (1836-1913)

When I was growing up on the Lofgren Home Place, an amateurish oil painting hung on the wall showing a small brick-red log house with white trim and a flagpole in front. I never thought much about it, except that Ida said her mother had been born in that house, and it was in Sweden. It was only in going through Ida's writings about family history that I learned that the house in the by of Barrud had been in the family for many generations, and was still occupied by cousins. When we visited Sweden in 1984, and found our way to Barrud, I experienced the interesting shock of entering into the old painting: the house was painted the same color, only brighter, and the old flagpole was still there. It was much better, though, because I could look at the parts that weren't in the picture: the pleasant interior (but how could my great-grandparents have raised 5 children in a four-room house?), the cliché Old Oaken Bucket well in back of the house (still used for all the water needs of the house), and the outbuildings: a barn, machine shed, and the most elaborate wood-paneled outdoor toilet I've ever visited (also still used). The photo shown here of the house (sent by Alf) is probably the source for the oil painting. The location of the house is shown on the 1870 Barrud map. I would like to have thought that the re-entrance into the old painting was not just an illusion, that I had somehow taken a time voyage, but of course I had not. There were cars all around, and a tractor in the machine shed. Johan Oskar's grandchildren, who live there only during the 5-week summer vacation that's standard for Swedes, take great care to preserve the Barrud house just the way it's always been. Someone in the neighborhood still grows strawberries on the land, but the grandchildren, Bernt (a banker in Malmö) and Alf (who worked for Swedish Railroads in Örebro, is now retired and winters in Skövde) do not. In fact, the residents, who have inherited these houses from the old folks, spend only those summer vacations, plus some nice weekends, maintaining the houses in their pristine condition, at Barrud. It's almost a ghost town the rest of the year. It would be an outdoor museum if it were listed on a map anywhere. Their mother, Birget, lived nearby, in Finnerödja, until she died in 2002.

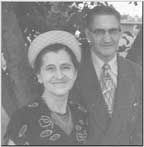

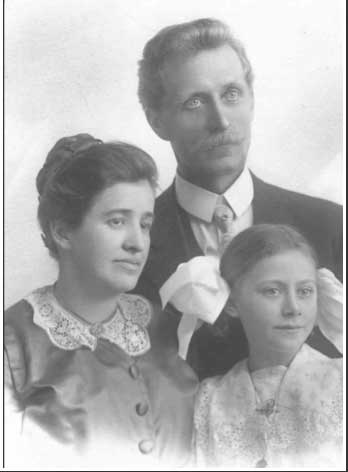

From Ida Lofgren's notes: Mother (Ida Lowisa) worked in Finnerödja at a finishing school. Parents with means would send their young girls to this school. They had teachers for the Three R's, but they also had to learn to weave linen and wool; prepare sheep wool, card and spin, etc.; make soap, both soft and hard; cut patterns. Mother and another girl took care of these students and also showed these things -- knitting and crocheting too. When these young ladies graduated from this school, they were ready to marry the better class men. Ida Lowisa and August finally came to America in 1893, and Adolf followed in 1907. Adolf didn't like it here, so he moved back to Barrud in 1908 and built a small blacksmith shop that is still standing. Alf Gunnarson showed us the steamer trunk he took to America and brought back with him which is preserved in the family house at Barrud. Adolf, the returned but non-prodigal son (none of our relatives have ever been accused of being wastrels), is in the picture, circa 1910, taken in the living room of the Barrud house. He's on the left. Continuing to the right is my MMM Gustafwa Jonsdotter Karlsson; great uncle Karl Karlsson; Augusta Fransson Karlsson; and her husband, my great uncle Johan Karlsson.

|