|

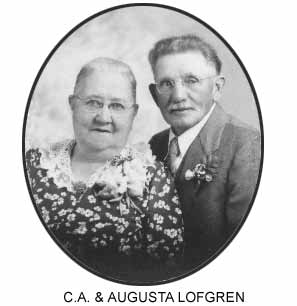

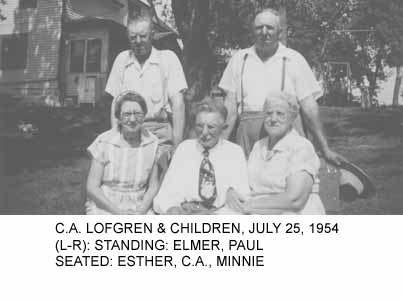

9. SECOND GENERATION (LOFGREN): (9.1) C. A. Lofgren ( Sept. 19, 1863-Sept. 23,

1958 ) = (9.2) Augusta Johnson (June 7,

1868-Mar. 24, 1948) on August 31, 1884

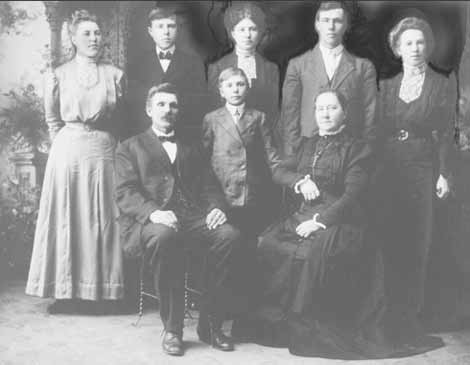

About midway during his stint as a section boss in Minneapolis, C.A. and Augusta got married. C.A. was transferred to be section boss on the Wyoming-Taylors Falls spur line in 1885. They lived in a section house in Wyoming, where Augusta cooked for the crew, until 1887. Jennie and August were born there. In 1889, they moved to a section house in Center City, where Minnie and Esther were born. Sometime before 1888, C.A. bought 80 acres in Harris township (the forty that includes Goose creek and the next one to the east) in Section 8 (location #6, Harris, 1888). At some later time, he bought the next forty to the east, so the complete farm, which I will call the "Lofgren Home Place," was 120 acres. On January 1, 1894, he quit the railroad, and on April 24 of that year, after having lived with Johan Johanson's, they moved into the new house they had built. Elmer and Paul (as well as Mike and I) were born in that house. C.A. went $2000 into debt to buy the farm (big money, back then), but was lucky enough to have a good crop the first planting year, and was able to pay it off quickly. Clearing the land took several years, though. On the occasion of C.A. and Augusta's 25th wedding

anniversary, in 1909, they had a family portrait taken. The Lofgren Home

Place: The cookstove was fired up every day and made the kitchen cozy enough in winter for baths in a galvanized tub with water heated in the stove reservoir. Of course "bathroom" wasn't even a concept. The toilet was out by the woodpile.

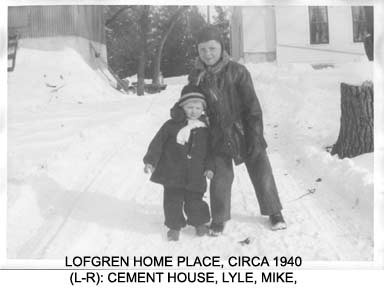

We had the usual outbuildings, constructed as the need

arose: pig shed, chicken house, horse barn, granary, cow

barn, silo and windmill-what you'd expect on a

small-time dairy farm before the advent of bulk tanks

and grade A milk. We also had a couple of unusual

structures. The "cement house" is a small 2-story

thick-walled concrete building near the house. Our

windmill pumped water into a wooden tank in the upper

story and gravity sent running water below the frost

line to the house, cow barn and horse barn. A concrete

water tank in the lower story stored water for the

cooling milk cans, and created a cool, moist environment

for household perishables. For reasons that were never

clear ("jealousy" was all Elmer would say about it),

construction of this cement house had something to do

with intensifying the dislike between Charlie Johnson

and the Lofgrens (see chapter 8).

Perhaps Charlie thought C.A. was getting too big for his

britches. The ingenious water tank fed the first

automatic waterers to be found in a Harris cow barn.

Another bone of contention was that C.A. favored a

proposal to continue County Road 9 straight north

in a line with its direction out of Harris, rather than

its previous route, which followed high ground

kitty-corner through his western forty (Harris, 1888). Charlie

opposed this, as the road would take some of his land

away. The road was built (now called Galaxy Avenue!),

after which, per county tax records, C.A.'s eastern

forty consisted of 51 acres. And you wonder why Charlie

was mad? Alternate explanation: I talked to Tommy

Johnson, Charlie's son, about this. He said the main

problem, at least with Augusta, was that she took

August's side in the dispute about August assaulting

Charlie (see below).

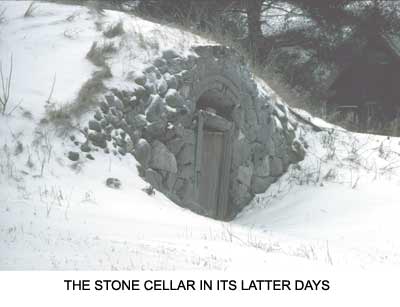

Another unusual structure on the Home Place was the "stone cellar," a root cellar built of unmortared fieldstones skillfully formed into a cavern. The stonemasons first built a wooden framework, then piled stones over it to form a domed enclosure. Then they called the enfaldig-the slow-witted one-and sent him into the cave to knock out the post on which the whole structure depended. It went just as planned: the stones locked into place on the principle of the keystone arch, and the enfaldig survived. Covered with earth, the structure made a mound about 10 feet high-our winter sledding and skiing hill. The mound was truncated at the front by an exposed fieldstone wall with a door. An engraved brick above the door gave the construction year: 1899. Three more serial doors led into the dark interior of the cave that kept an even temperature summer and winter. We stored potatoes, cabbages, carrots, rutabagas, and turnips where they kept well without sprouting. It also made for a great shelter in a storm. I think Elmer was an alarmist when it came to storms. It seems pretty often he routed me and Mike out of bed in the middle of the night and ordered us to follow the family single file. One time, though, I remember the lantern throwing huge shadows while wind in the white pines roared like a runaway train and broken branches flew through the air all around us. That project went so well that C.A. decided he and Elmer could build a concrete cistern beside the house to catch rainwater runoff. They built a wooden form to prop the cement until it dried. When they were done, C.A. grabbed the sledgehammer and said he'd go down into the cistern and knock out the struts. "You better not do that," cautioned Elmer. "You're not an enfaldig and we can't spare you." Hearing them arguing, Augusta, alarmed, came outside to plead with C.A. While she kept C.A. distracted, Elmer grabbed the sledge and knocked the wood frame apart without climbing inside. The cement slumped into the cistern. That's one time accident-prone C.A. didn't get hit on the head. Elmer saved him. When they rebuilt, they made the concrete walls twice as thick. Besides 3 bedrooms upstairs we had an unheated attic area that we called "Up-Over-The-Kitchen," because that's where it was. Another funny thing about the house were the ornate hot water radiators. All the while I was growing up the house had no central heating but apparently at one time C.A. had installed a system with piping. The wood furnace in the cellar turned out to take a lot of wood, and was hard to regulate, either running too hot or too cold, and likely to burst the pipes. In my time, the kitchen was heated by a wood cookstove and the dining room and living room were heated by a wood "heater stove." The kitchen and bedrooms were the only rooms that were used much, anyway. After supper, we'd light the Aladdin lamp and the whole family would sit in its light. Women did handwork, Elmer read the newspaper, and Mike and I did our homework. The woodpile was a constant obsession of Elmer's. His mood depended on the size of the pile and if it fell below a certain level, Elmer got very depressed. It's not surprising since survival depended on the wood supply. Even after he could barely shuffle along with his cane, Elmer could still split wood with just the weight of the axe, an ability honed by long habit. Our city-raised kids tried to help him out in his old age, but missed and chewed up axe handles, which drove Elmer about crazy. Mike and I slept upstairs in one bed to keep warm. In winter, after supper we would build a large fire in the Round Oak stove to get the room up to about 40 degrees so we could get in bed. One year, a traveling salesman convinced Elmer that we should blow rock wool insulation into the walls and roof. The night after the house was insulated, we built a fire in the bedroom stove as usual, and when we went up to bed the thermometer read 130 degrees. A dramatic demonstration of the efficacy of insulation. Even after insulating, the upstairs was hot in summer, and the windows had been painted shut, so Mike and I slept on a bed in the front porch. The screening had holes, so we were bothered by mosquitoes, but it was at least cool. Even though the tracks were a half mile away, if the wind was from the east blowing up rain, the whistle from the night train was so loud that I often dreamed that it was coming right into the house. The last of the outbuildings was the unpainted machine shed that's still standing on the north side of the group of buildings. Brother Mike and I helped C.A. build it when he was in his late 80s. I tried to verticalize a long 2 X 4 by picking up one end and walking towards the middle. I lost control as it overbalanced and it conked him on the head, rather hard. It brought him to his knees, but he got up in a minute or so. Influence of the Railroad: The St. Paul and Duluth Railroad was completed in

1870 and purchased by the Northern Pacific in 1900. In

the early days, Harris was the Potato Capital of

Minnesota. Before the railroad went through Cambridge

in 1899, most of the potatoes from that part found

their way to Harris. At times a whole train was made

up in Harris to be shipped to Chicago or St. Louis.

Buyers made their headquarters in Harris. There were 4

warehouses. (I now see where I got my writing style that consists of combining random facts in no particular order.) The morning St. Paul Pioneer Press was the dominant newspaper all along the Northern Pacific St. Paul-Duluth line, because the newspapers would be sent on the night train and delivered by the mail carrier the next morning. Paul Lofgren subscribed to the Minneapolis Star, but he didn't get the paper until the next day, because it had to be shipped from Minneapolis to St. Paul, then transferred to the Duluth train. Even the Minneapolis morning paper would have arrived a day late. I figured he must be really mad at the Pioneer Press to put up with day-old news, but now I think it had something to do the comics they carried. Because of the train and newspapers, St. Paul was our major influence. On the rare occasions Elmer took us to an AAA baseball game, it would be to Lexington Stadium to see the St. Paul Saints. He had been a pitcher on the Harris baseball team in the early part of the century, so baseball was a real thrill for him. Even with the coming of the automobile, Highway 61 followed the NP tracks. The Forest Lake Cutoff (Highway 8 to Minneapolis) wasn't built until the late 1930's. It was intended to be a big improvement: three lanes instead of two. You could use the center lane for passing. It took them awhile to figure out that it's not the best idea in the world to have a center lane for passing from either direction. There were lots of head-on collisions. It wasn't reconfigured as a two-lane highway with extra-wide lanes until the 1950's. Its remains are now mostly obscured by I-35W. Highway 8 was a convenience for us to visit Minneapolis relatives, such as Marina Larson. My mother Ida, who was familiar with Minneapolis, took the Greyhound to shop there. But usually, if you went to stor stan (big town) to go shopping, you were going to St. Paul. The ghost of the old night train still remains: the St. Paul paper retains a presence in all those towns along the old NP track, just as the Minneapolis Star Tribune is about the only paper you'll find along the rail lines that once emanated from Minneapolis. Elmer had a great respect for trains and sometimes went to a track crossing and hailed the train to a stop so he could hand a bunch of newly pulled carrots to the engineer. C.A.'s Mishaps One time C.A., Elmer and Paul were clearing some land. They did this by grubbing away the dirt from around a standing tree, then chopping all the roots, tying a rope up the tree as high as they could and using a team of horses to pull the tree over, roots and all. As the horses began to pull, someone had to run along behind them, hanging onto the rope in order to keep the force angle from lifting the horses' hind feet off the ground. Paul was driving the team, Elmer was holding the rope, and C.A. was supervising the operation, but the tree wouldn't yield. C.A. decided to take over the rope detail. "Be sure to let go," said Elmer. Paul urged the horses on especially strong, and C.A. did indeed let go, but a little late. The straightening rope threw him about 12 feet into the air, where he hit his shoulder on the branch of another tree, then fell back down on the ground, out cold. Thinking he was dead, the sons loaded him on the wagon and drove him home. Augusta saw them coming, came out of the house and looked at him, saying, "Now you've done it! Now you've killed him!" Just then, C.A. revived, none the worse for wear except for a dislocated shoulder. Then there's the disk harrow story. The driver rode on a seat that extended in back of the disk, attached by a semi-flexible strap of spring steel. The seat support broke. C.A. was proud of his blacksmithing ability, particularly his ability to apply the proper temper to steel. He got out the forge and anvil and his smithy tools and welder's sand (pure white quartz sand from the St. Peter Sandstone formation) and bucket of quenching water for the tempering operation. The family gathered around as he finished welding the two pieces of spring steel together and reattached it to the seat and the disk. He proudly sat on the seat, which promptly bent down to a vertical position, dumping him off, then sprang back into its original position, awaiting the next victim. Of course, all the children fell on the ground laughing, as C.A. said, "That wasn't funny!" He pounded the strap and seat to pieces, then went into town to buy a new one. Another story has him accidentally hitting his thumb with a hammer, after which he turned his thumb sideways, and hit it again, evidently to unflatten it, or perhaps impress those watching how immune to pain he was. In fact, he seemed to get hurt almost every day, and often walked around with a red handkerchief wrapped around his hand to stanch some wound, such as those caused by chickens who, when he was picking eggs, would regularly turn around in their nests, grab a prominent blood vessel on his hand, and pull until the blood flowed. That wasn't as severe an insult, however, as the time he blindly reached into a hen's nest, only to find it occupied by a skunk. They buried his clothes. He would have been in his forties or fifties when automobiles first appeared, but C.A. did not hesitate to drive one. In my early recollections, he and Augusta drove a 1937 Studebaker. They would go to town to shop, but sometimes end up in the ditch. One such mishap occurred because a mouse ran across the dashboard and C.A. tried to catch it without bothering to stop the car. In 1941, the family bought a 1940 Pontiac, which had the shift lever on the steering wheel. C.A. and Augusta went for a spin with it, returning hours later. Neither would say what happened, but C.A. never drove again. C.A., a music lover, bought a pump organ and tried to learn to play it. He was unsuccessful, either because he was too old, or because he had no talent for music. He also sang, even though, as Ida Lofgren said, "you could peel potatoes with his voice." It was one of the few failures in a life that usually consisted of success brought about by combining ingenuity, cleverness and stubbornness. His love of music did produce some results in the next generations, however. Elmer played fiddle and harmonica, and many of C.A.'s descendants play musical instruments or sing. He was healthy and strong most of his life, but C.A. was a confirmed hypochondriac. He was particularly convinced that his intestinal system was sick, that he never slept and that he hardly ate at all. The other family members noticed that he slept and ate quite a lot. He tried every patent medicine he read about: Hoffmann's Drops to fix his heart and Doan's Pills to stimulate his kidneys. The latter must have been effective, because it turned his urine bright blue. He ate sand by the spoonful to supply needed roughage, and drank dilute muriatic acid to add to the acidity of his stomach. He sipped the acid through a glass straw so he wouldn't dissolve his false teeth. That naturally caused an acid stomach, which he treated by drinking baking soda dissolved in water. As any high-school chemistry student knows, acid combined with baking soda produces carbon dioxide gas, which made C.A. belch prodigiously. Troubled with ingrown toenails, he went to University Hospitals in Minneapolis to have an operation to remove a strip of nail from the center to narrow its growth. Some nincompoop forgot to remove the wire that had been wrapped around his big toe to stop the bleeding. Without blood supply, the toe swelled into a huge lump of proud flesh. That was before anyone could sue for malpractice. C.A. just cut a piece off the top of his shoe to allow room for the toe, and made the best of it for the rest of his life. For all his toughness, certain things bothered him greatly. If a cow switched him in the face (which, after all, is how a cow expresses her affection for you), he'd pound the cow mercilessly with a milk stool. In the beginning, they only had two cows, so they couldn't really afford to have him losing his temper over such things. As a result, he never milked, and never entered the cow barn at milking time. C.A.'s training methods seemed to work better with our horses. Mike was only 8 when C.A. sent him to cultivate the potato field with a team. Though harnessed with an older, quiet mare, the young green horse kept bolting with little Mike hauling on the reins for dear life. C.A., observing the transgression, wrenched a fencepost out of the ground and hit the horse over the head. The horse went down and stayed there for five minutes until Aunt Esther poured a bucket of water over its head and it revived. That refined the training of that young horse. It never tried to run away again. C.A. was a Mason, and took the Masonic Rites seriously (Chapter 6) . He had a small book, written in secret code, that he studied regularly. He would let no one else look at it, evidently for fear one of us would be able to crack the code. He had a serious shortcoming: he never learned to tie a necktie. Augusta always tied it. One night, he went to Rush City for a Masonic Lodge meeting, and that night was inducted into the 3rd degree, which required him to remove his shirt. When he returned home, he was not wearing his tie, and Augusta, of course, suspected the worst. Even though he was in the doghouse for a long time, C.A. never told Augusta why he'd taken off his shirt, as it was part of the secret rites. The Smith Place:

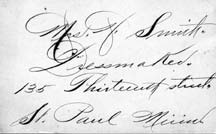

For some reason, they'd forsaken the city, but they had big plans for their farming future. I once found a journal, in Mr. Smith's florid handwriting (see Mrs. Smith's business card, above), where he planned his dairy herd. Buy a pregnant cow which would have twins. Those twins would each have twins within two years, and in a surprisingly short time, he would have a large herd. He painted a sign that read MIDWAY JERSEY STOCK AND DAIRY FARM, so named because Harris was sort of midway between St. Paul and Duluth, and thus could ship enough milk to satisfy both cities. Minneapolis would have to wait. They must have started out with some money (perhaps from Mr. Carter's life insurance?), since they bought the three forties of land, built a house on the middle forty (still standing), a house and small barn on the north forty for Bill (called, of course, "Bill's forty"). Unfortunately, neither the bovine twins nor the ingenious automatic egg collector Mr. Smith invented worked out. The twins were never born, and the eggs broke after rolling down the inclined plane. Then, one night after Mrs. Smith had died, Mr. Smith awoke to see something at the foot of his bed. "It was either my wife or the Devil," he later explained. Either way, he woke his sons, and they left immediately, never to return. August Lofgren bought Bill's forty, and, later, C.A. bought the haunted house and the middle 40. After Elmer and Ida were married, C.A. and Augusta moved into it from the Lofgren Home Place. The Smith dream ended with Rob Carter living alone on the southernmost 40 acres in a tumbledown house that Smith built after the spook chased him out of the original one. We used to buy groceries for Rob, and, in the winter, carry them to him through the woods on skis. I liked him because he made fudge, had good stories to tell, and (incidentally) always gave me cigarettes to smoke (I was about 12 or 13 at the time). He showed me some of his old paintings, which were conventional landscapes. Carl Lofgren bought the last forty after Rob died. The Smith House had no basement when C.A. and Augusta moved there. It was set on posts and had an 8 foot deep square hole dug in the dirt to store canning jars and potatoes. To get down there, you had to lower yourself through a trap door in the kitchen onto a step that was actually the top of an old worn-out stove, then climb down off that to reach the shelves. After Mrs. Smith broke her leg trying to get down there, Mr. Smith nailed it shut. They'd been living there about a year when C.A. decided to dig a basement. First they had to move the house so it lined up north and south parallel to the road. Then the men dug a tunnel in one side and out the other wide enough for a horse and slush bucket. C.A. had a horse named Bud. He figured Bud wouldn't want to go down the hole so he tied a gunny sack over his eyes and led him down. Their wasn't much clearance so Bud hit his head on the bottom of the house. C.A. whacked Bud behind the legs so he'd go down on his knees and had to crawl out the other side. After a couple practice runs, Bud had the hang of it so they hitched him to the slush bucket which could be set to scrape up a load of dirt and dig the tunnel deeper. As soon as they had enough room, the men went in with shovels and filled the bucket with dirt from the sides of the tunnel. Things were going well, so C.A. took the blindfold off and found that Bud did even better when he could see. Pretty soon Bud was going down the hole at a run as soon as the load was dumped. The horse learned so fast, Grandpa threw the reins away and they got the whole cellar dug in a day. Bud had a trick where he'd herd city guests into a fence corner and rear up over them, scaring them half to death. He was real careful not to hurt anyone. If they weren't scared out of their wits the first time, he'd quit, but if he had them cowering, he'd keep rearing. He also could bring the cattle in just like a sheep dog. Poor horse died of sleeping sickness. Stromberg's Washout:

The Strombergs farmed some land on the bluff above the St. Croix valley about 4 miles out of Harris. Two unmarried brothers and an unmarried sister, they did evolution a favor by not reproducing. Right near the south side of the house is their greatest folly, the washout that sucked their farm away. It didn't used to be there, but around the turn of the 20th century they decided to drain some swampy land by plowing a furrow across the brow of the bluff. Except for a few inches of darkish dirt on top, the whole bluff is sand, originally from the bed of Glacial Lake Grantsburg which caught the melt water from a lobe of the last departing glacier. After the ice dam broke, Lake Grantsburg disappeared down the St. Croix river. Winds picked the sand up off its dried bed and blew it all around Chisago and Anoka County. That was only a few thousand years ago and that's why the fertile topsoil is only a thin veneer. The drainage project was so successful it drained their swamp, and other swamps from miles around, taking a good portion of shallow topsoil along with it. The furrow broadened and deepened into a chasm that's now about 50 yards wide and 100 feet deep; a crease in the bluff, a shortcut to the St. Croix. After the Strombergs died, we used to trespass on their land, now owned by Chisago County, to pick morels in the spring, jump off the edge of the ravine into the soft sand bank, look into the dangerously dilapidated remains of their house, and collect the empty whiskey bottles they had thrown in the general direction of the washout, perhaps in a futile attempt to fill it up. We tell Stromberg stories decades after they occurred because they illustrate something enduring, recurring and funny about the human condition. As examples of human fallibility, the Strombergs are stock characters; they play the fools, taking pratfalls in our stead. As someone said, everyone has a purpose on this earth, even if it's only to serve as a bad example. Here's another one: The Strombergs had a dog that had gotten long in the tooth and they decided to help it along into the great All Of Being where individuality merges with the infinite and time is swallowed by eternity. At first one of the brothers thought of shooting it, but the other nixed that idea as too cruel to witness. Instead, they led the dog out to a patch of woods, tied it to a tree and attached a stick of dynamite to its neck. They used a long fuse so they would be far away when the stick went off. They lit the fuse with a kitchen match and high-tailed toward home. The dog, who didn't want to miss the action, pulled loose and followed them. They yelled at him to get back, but that dog was a sentimental old fool and loved them dearly, so he ran along behind them in his crippled way and managed to keep up pretty well considering his arthritis and hip dysplasia. The brothers got to the barn just in time to slam the door in the poor dog's face. He hung around the door a little while, whining and scratching. The brothers could hear the fuse just a-sizzling. They cursed and yelled at the dog till he felt so ashamed and rejected that he slunk over to the house and crawled under the porch where he was accustomed to lie in the heat of the day. By that time, the fuse had gotten short and the fumes burned his nose. Frantically, the dog managed to paw himself free. He crawled out from under the porch just as the sister came to the door to look out and see if her brothers were back. Surprised to see the dog trotting towards the barn, she had just begun to wonder how come, when the porch blew off the house. The dog stayed hooked to the phenomenological world for several more years and for all I know may have outlived that threesome of knuckleheads. Diaries: You won't find their personal desires written in spare time on winter nights. Instead, Jennie filled a whole notebook in pencil with hackneyed words to maudlin songs: O mother mother, you don't know but we'll never learn what sorrows pained Jennie who died so young, only 35, of Tuberculosis, just after she bore baby Clarence. Esther filled a notebook with recipes, riddles and lists of facts. A farmer was asked how many pigs he had. "If I had so many pigs more, and half as many more, and seven to boot I should have 32." She diagrammed the solar system, and copied out the remedies for diphtheria, quinsy and croup, even told how to clean a bear skin. The SysteMentry Year Book and Calendar was distributed nationwide by local banks. The back of each page of numbered days in the month was meant to be a woman's account book. It had columns for poultry, eggs and cream, all the province of women. Grandma Augusta didn't use it that way. Instead, she wrote a line a day across the columns. A line at a time didn't leave room for rumination. Examples from 1917:

Jan. 21, Blizzard worst in History. Elmer to Smiths. Boy! If the mailman couldn't get through it was a big deal. Meanwhile babies are born and people die on the same lines as seed potatoes are prepared for planting. So impersonal. I don't know about other families, but Lofgrens kept track. Elmer recorded the date and weather in pencil on the storm window frames in the fall and on the screen frames in the spring. Augusta kept the diary of 1933. She and C.A. were living on the Smith Place. She wasn't feeling real well in her 65th year, and actually spent 2 days in bed. Grandpa turned 70. Reading how the work got done reminds me of a by in Sweden. Pauls' on The Day Farm, Elmers' on The Home Place, and August's family all did the farm work together. The September before, August fell out of the butternut tree and broke his back; he died in December (see below). Carl ran that farm, but you wouldn't know it from this diary. In January she writes: Eggs 10 cents a dozen. I dreamt I seen and talked to August first time. On March 11: again, I dreamt I saw and talked to August last night. Same dream the next night. You can tell it's a hard year since C.A. has to buy both corn and oats. Audrey, Marion and Marina are in their last year of high school and board with families in Rush City during the week. Someone brings them home by horse and sleigh for weekends: usually C.A., but often Carl. All three girls catch the measles in April. The whole family goes to Rush City to see the 3 girls perform in the school play. C.A. buys a team of horses for $165 and sells them to Paul. Augusta starts a quilt block with a stork for a coming shower for Mrs. Hilbert Richard. Soon the pieces are ready for a quilting bee. One hundred people attend the shower. At Elmer's, two mare colts are born in the spring. At Paul's, Arvid has turned 7 and Jane 5. Elmer and Ida's child is just called "the baby" or "Kutten;" until the Oct 6th single line entry, Little Myron took kerosine so I took him to Dr. Whoever is free takes cream to The Co-op Creamery, but usually it's C.A.. The machinery breaks down, all 3 grain binders at once, and it takes several days to fix them. They must be renting land at Sybrant's because Paul gets the tractor mired there in May but they're still doing most of the work with horses. The girls clean the chicken house, cut potatoes and plant them and Elmer sprays the plants with Paris Green. April 13, Augusta sets 2 hens on eggs from Paul's and on May 11, 3 more hens on eggs from Griggs. C.A. is still blacksmithing. He shoes horses at Paul's, makes a wheelbarrow for Elmer and a rack for Carl. The men butcher beef at Paul's and hogs at The Home Place and Ida and Augusta can beef and chicken. The Men cut down 3 trees on the home place. In February they have a husking bee. Not a day goes by that Es, or El. & Ida don't visit, or maybe Augusta walks through Herring's woods to Paul's for dinner. On the cardboard back of the calendar Augusta reports what she hasn't had room for on the line-a-day. Mrs. Albin Johnson and 7 children burned in the middle of the night. Their heads are found buried in a nearby field. Mr. Johnson's body is missing and volunteers search for him. Foul play is suspected. There's an inquest in Harris. On May 1st it's reported he's been seen in Montana. In the end, Johnson is not found and no murderer is jailed. In May, 15-year-old Carl sows alfalfa on his Dad's farm. Potatoes are 25 cents per 100 lbs. Hope for better times. On May 28th the Studebaker is stolen by a hired man and turns up at the police station in Minneapolis. Had run hundreds of miles and most of the tools and emergency kit gone. After Grandma died, Ida took up the practice. Esther kept a diary when she and Claus lived on Maryland Ave. in St. Paul. Marina wrote in those 5 year diaries that lock with a clasp and kept it up from the time she moved to Minneapolis in 1933 until she died in 2000. Schooling The girls were a different case. Not needed on the farm, unmarried, they were a liability-more mouths to feed. While immigrants in the cities scrimped to send their boys to school, and thought girls didn't need schooling to take in wash, on the farm the opposite view prevailed. Audrey, Marion and Marina vied all through school for top marks and all 3 went to the city for further training-Marion as a nurse, Audrey and Marina to business school. The same was true for the unmarried Swenson women. Ida went to business school and her sister Svea was a nurse during WW1.

C.A. and Augusta's

Later Years: Other advice C.A. gave to Mike: "There are two people you can never trust: a preacher or someone who sits in the front row at church." "If you've got cowshit on your boots, you can always borrow money at the bank." I have a feeling that cowshit collateral isn't as effective as it once was. In her later years Augusta reportedly made peace with her brothers, except for Charlie. She also developed diabetes, and I, being of a scientific bent, learned the daily task of testing her urine for sugar level and giving her insulin shots. Later, she had a severe stroke and was in a coma for a long time before she died. After that, C.A. moved back into the Home Place, leaving the Smith place empty for many years. C.A. was energetic and bright into his mid-90s, until

he, too, had a stroke, and had to spend his last days in

a nursing home. |